Deep reinforcement learning in operating OpenAI.gym lunar lander

10 Aug 2021The purpose of this project is to explore the power of reinforcement learning in training a simulated Lander agent to land on the moon surface. The implementation of the agent utilized function approximations to adjust the weights of underlying models during training phase, instead of using tabular approaches typically for discrete state or state-action spaces.

This is the beauty of deep reinforcement learning and reinforcement learning in general, which might be able to achieve general artificial intelligence. A reinforcement learning agent does not rely on models (model-free), and it can learn from interactions/experiences with either physical or simulated environments. This also means that reinforcement learning does not rely on labels or pre-existing data. It can learn from scratch with zero experience.

A successful trained agent can land the rover in the simulated environment, seen below:

Figure 1. Successful landing in simulated OpenAI gym using trained deep reinforcement learning agent.

Experiment set-up:

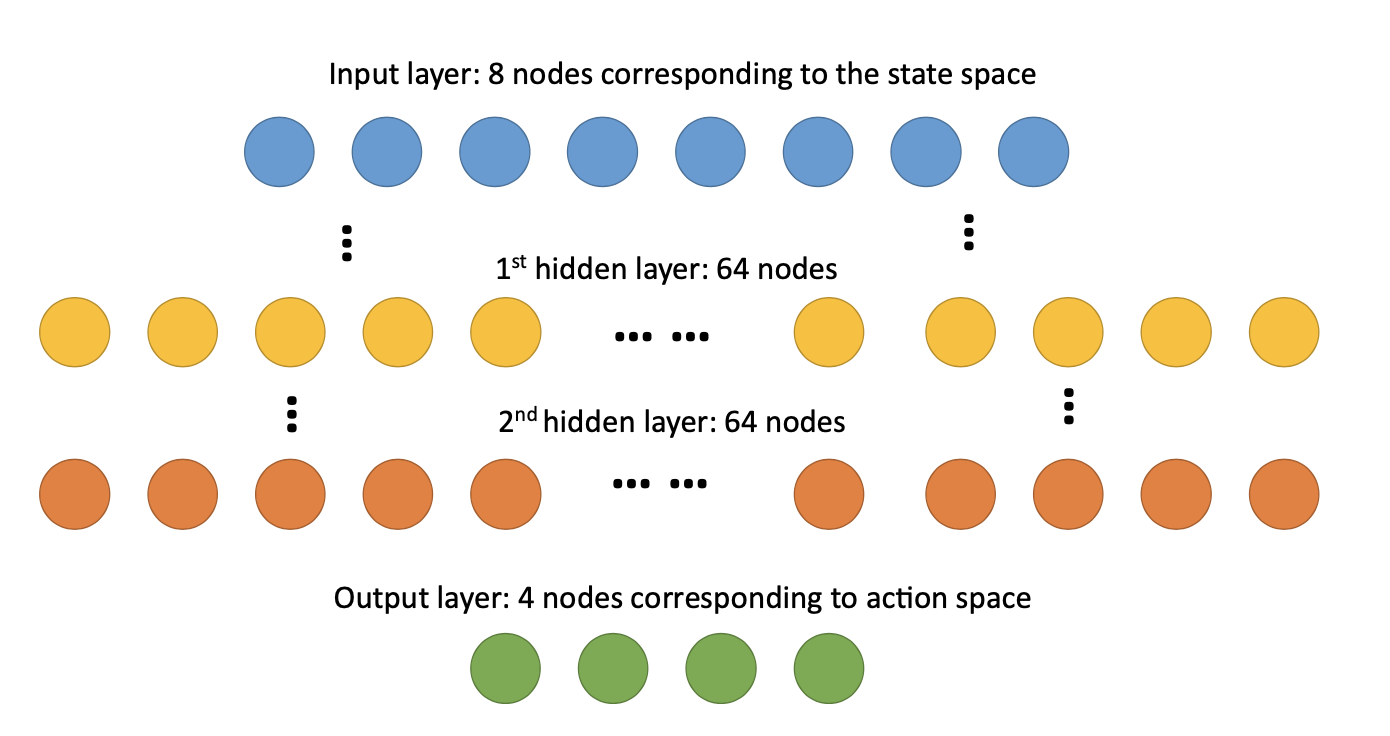

The environment used in this project is from OpenAI gym [1]. The lander agent interacts with the simulator for tens to thousands of episodes. It is an 8-dimension state space with 6 continuous states (position x, position y, velocity x, velocity y, angle, angular speed) and 2 discrete states (left leg ground contact, right leg round contact). Due to the continuous state space, tabular approaches such as Q-table would not be efficient, even though it can be done by proper discretization with sufficient domain knowledge. This type of problem is more suitable to use function approximation as the underlying model to generate value functions or actions. In this case, a neural network (NN) was chosen to map the 8-dimensional state space into Q values corresponding to 4 actions (do nothing, fire the left orientation engine, fire the main engine, fire the right orientation engine). NN setup is as follows.

Figure 2. Neural network setup used as function approximation for the RL agent.

The learning algorithm implemented in this project is based on the DeepMind’s paper in 2015 using deep Q-network (DQN), combining reinforcement learning with deep neural networks. [2] In order to improve the performance of the RL agent, experience replay and a separate target Q-network in addition to the main Q-network were implemented as well in this project.

However, due to the ambiguities in the algorithm listed in the DQN nature paper, two major interpretations were made in this project to resolve the problems faced during implementation.

First, instead of using the target Q-network’s full predictions to fit the agent’s main Q-network, only Q-value prediction corresponding to the action selected from the experience replay, combined with prediction from main Q-network, is used in fitting the Q-network. [2] Second, schedule for copying main Q-network to target Q-network is set to be after every episode, instead of every C step specified in DQN nature paper. Different C values (from 10 to 1000) were first explored, and the agent performance first improved and then deteriorated. After moving to the episode-based schedule (inspired by epsilon decay schedule), the agent performance is very stable and can reach convergence.

Detailed experiments and results were discussed in the following sections. Number of episodes and additional two hyper parameters, including learning rates and discount rates were studied in detail. Other hyper parameters, such as replay capacity = 5000, minibatch size = 32, epsilon decay schedule (𝜀_min= 0.1, 𝜀_max = 1, 𝑑𝑒𝑐𝑎𝑦 𝑠𝑡𝑒𝑝 = 200), and NN structure (Optimizer=”Adam”, Loss=”mse”) were held constant.

Experiment 1 – number of episodes. 2000 episodes were run for training the Lunar Lander RL agent with learning rate = 0.0001 and discount rate = 0.99. An evaluation of 200 episodes was done to test how the agent performs using trained policy or underlying function approximated Q-network to generate actions.

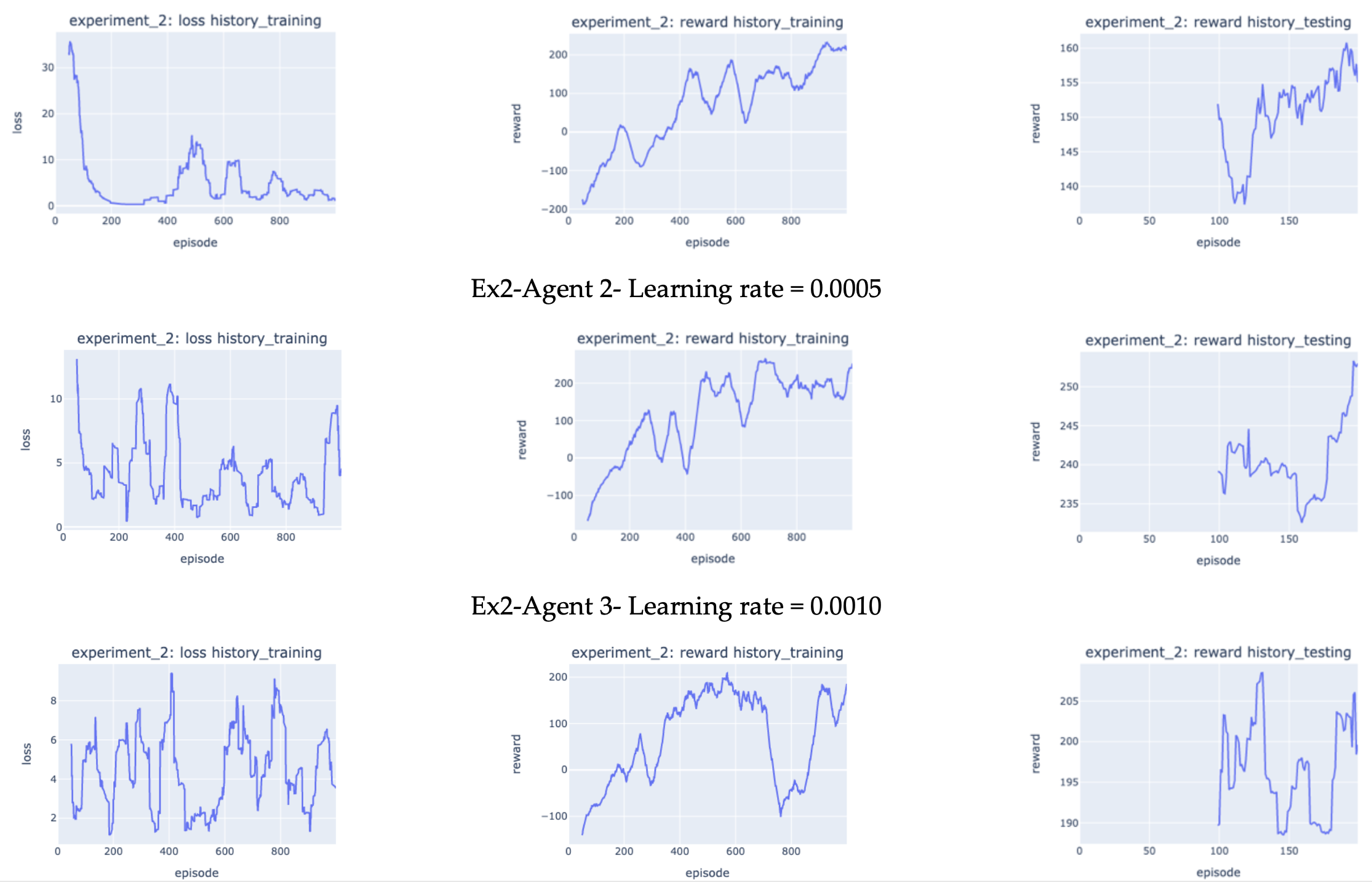

Experiment 2 – learning rates. Three learning rates were explored in this experiment, i.e., 0.0001 (Ex2- Agent 1), 0.0005 (Ex2-Agent 2), and 0.0010 (Ex2-Agent 3). The discount rate was held constant at 0.99. Training episodes of 1000 were run for fitting the Q-network for different learning rate settings. Similar to Experiment 1, evaluations of 200 episodes were run for each setting.

Experiment 3 – discount rates. Three discount rates were explored in this experiment, i.e., 0.99 (Ex3-Agent 1), 0.90 (Ex3-Agent 2), and 0.80 (Ex3-Agent 3). The learning rate was held constant at 0.0001. Training episodes of 1000 were run for fitting the Q-network for different learning rate settings. Similar to Experiment 1 and 2, evaluations of 200 episodes were run for each setting.

Results and analyses

(Ex1) Effects of episodes. Figure 2 shows the result how the agent performed during training and testing. During training, based on the loss history during training, the error during training decreased drastically in the first 500 episodes. Then the error plateaued and oscillated around 2.5 from 500 to 2000 episodes. One reason for the fluctuation was due to the randomness in the starting position of the rover and epsilon- greedy actions during training, where the minimum epsilon is set to be 0.1. Looking at the reward history during training, even though the error converged after 500 episodes, the average reward (50-episode rolling mean) is still less than 200. However, as training continued, the agent performance got a huge boost in to 200 reward range, indicating number of episode close to 1000 is needed to train an agent with good control of how to land the rover. As number of episodes increased from 1000 to 2000, the agent performance did not improve significantly, indicating longer training episodes are not needed under current training settings.

In order to study the performance of the RL agent after 2000-episode training, the agent was evaluated only using trained Q-network. The average reward history during testing with 100-episdoe rolling mean was plotted in Figure 3. It was found that the 100-episode average rewards are constantly above 200 from testing episode 100 to 200, indicating an agent with satisfied performance.

Figure 3. Experiment 1 results (left to right): training loss history (50-episode rolling mean), training reward history (50-episode rolling mean) and testing reward history ((100-episode rolling mean).

Based on the result from Experiment 1, episodes were selected to be 1000 for the following experiments.

(Ex2) Effects of learning rates. Figure 4 shows the result how the agent performed during training and testing with different learning rates. During training, based on the loss history during training, the error during training decreased drastically in the first 200 episodes for all settings to be in the range of 0 to 10, the plateaued for the rest training episodes. In particular, with increasing learning rate, the episodes it took to converge decreased. This is due to the fact that, a faster learning rate in the optimizer leads to large step size during training, which requires fewer episode to converge.

The disadvantages of too slow and too fast learning rates were shown by the agent reward history during training and testing. After 1000-episode training, Ex2-Agent 1, Ex2-Agent 2, and Ex2-Agent 3 averaged (50- episode rolling mean) around 210, 250, and 190 reward, respectively. In addition, after 200-episode testing, Ex2-Agent 1, Ex2-Agent 2, and Ex2-Agent 3 averaged (100-episode rolling mean) around 155, 260, and 200 reward, respectively. These results indicate, agent with slow learning rate needs more epochs or episodes to find the more optimal solution as the model converges slowly. On the other hand, agent with fast learning rate risk finding the sub-optimal solution, even though in this project the agent performance is still satisfactory.

Figure 4. Experiment 2 results: training loss history (50-episode rolling mean), training reward history (50-episode rolling mean) and testing reward history ((100-episode rolling mean).

(Ex3) Effects of discount rates. Figure 5 shows the result how the agent performed during training and testing with different discount rates. The result is quite interesting. During training, based on the loss history, similar to experiment 2, the error during training decreased drastically in the first 200 episodes for all settings to be in the range of 0 to 10, the plateaued for the rest training episodes. In particular, with a discount rate of 0.9, the final error is nearly zero.

However, the reward history during testing under different discount rate differed significantly. After 1000- episode training, Ex3-Agent 1, Ex3-Agent 2, and Ex3-Agent 3 averaged (50-episode rolling mean) around 190, -100, and 25 reward, respectively. In addition, after 200-episode testing, Ex3-Agent 1, Ex3-Agent 2, and Ex3-Agent 3 averaged (100-episode rolling mean) around 157, -108, and -2 reward, respectively. These results indicate, discount rate played a significant factor in determining the agent performance. This makes a lot of sense, as a high discount factor would lead the agent to care more about rewards in the distant future than immediate reward. In the case of lunar landing, the reward function is set up in a way to give more rewards or penalties at episode ending, which is critical in correctly land the rover on the landing pad.

Figure 5. Experiment 3 results: training loss history (50-episode rolling mean), training reward history (50-episode rolling mean) and testing reward history ((100-episode rolling mean).

Further discussions

Based on the results from above experiments, with other parameters set with values in Section 1, the best performing agent was created with training episode of 1000, learning rate of 0.0005 and discount rate of 0.99. During testing, this agent (Ex2-Agent 2) achieved average reward ranging from 232 points to 253 points over 100 consecutive runs/episodes (100-episode rolling mean). If more time is given to tune the agent, discount rates higher than 0.99 can be explored to further boost the performance.

Looking at the how number of episode and discount rates affect the performance, they are related to the fundamentals of how a RL agent learns about the experiences and makes predictions that maximize returns. On the other hand, learning rate is related to how supervised learning works, in this case function approximation using gradient decent to train the neural network.

References:

- https://gym.openai.com/envs/LunarLander-v2/

- Mnih, V., Kavukcuoglu, K., Silver, D., Rusu, A. A., Veness, J., Bellemare, M. G., … & Hassabis, D. (2015). Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. nature, 518(7540), 529-533.